Sticky: Francis Kirkman The Lame Commonwealth in The Wits 1662 & 1673

The Wits, or Sport for Sport a collection of drolls (short plays) included one based on Act II Scene 1 of The Beggars Bush called “The Lame Common-Wealth”. This was adapted for informal and small scale performance anywhere. It may have been important in the distribution of Beggars Bush as a place name. At the very least it is an intriguing byway and example of the remarkable entrepreneurial career of the publisher Francis Kirkman. The frontispiece is widely reproduced, and inaccurately described, but demonstrates the popularity of the character Clause from the play & droll.

Francis Kirkman

Kirkman (1632?-1680) was the son of a London merchant. He appears in many roles in the literary world of the second half of the seventeenth century, as publisher, bookseller, librarian, author, & bibliographer. In each he is clearly not only an enthusiast for literature in all forms, but also a businessman, described by one modern editor as “hovering on the borderline of roguery”. Despite his wide involvement in the book trade he was never a member of the Stationer’s Company. Like his father he was a member of the Blacksmith’s Company, but is reported to have squandered a sizeable inheritance.

“Once I happened upon a Six Pence . . .”

In The Unlucky Citizen (1673) he wrote about being entranced by the chapbook histories when a boy, swapping them with friends;

“Once I happened upon a Six Pence, and having lately read that famous Book, of the Fryar and the Boy, and being hugely pleased with that, as also the excellent History of the Seven Wise Masters Of Rome, and having heard great Commendation of Fortunatus, I laid out all my mony for that, and thought I had a great bargain . . . now having read this Book, and being desirous of reading more of that nature; one of my School-fellows lent me Doctor Faustus, which also pleased me, especially when he travelled in the Air, saw all the World, and did what he listed . . . The next Book I met with was Fryar Bacon, whose pleasant Stories much delighted me: But when I came to Knight Errantry, and reading Montelion Knight of the Oracle, and Ornatus and Artesia, and the Famous Parisimus; I was contented beyond measure, and (believing all I read to be true) wished my self Squire to one of these Knights: I proceeded on to Palmerin of England, and Amadis de Gaul; and borrowing one Book of one person, when I read it my self, I lent it to another, who lent me one of their Books; and thus robbing Peter to pay Paul, borrowing and lending from one to another, I in time had read most of these Histories. All the time I had from School, as Thursdays in the afternoon, and Saturdays, I spent in reading these Books; so that I being wholy affected to them, and reading how that Amadis and other Knights not knowing their Parents, did in time prove to be Sons of Kings and great Personages; I had such a fond and idle Opinion, that I might in time prove to be some great Person, or at leastwise be Squire to some Knight.”

Kirkman was apprenticed to a scrivener, but seems to have converted his devotion to collecting into a trade as a bookseller in Thames Street, Fenchurch Street and St Paul’s Churchyard.

They that came into our Shop, might by the outside of the Books, imagine that we were well furnished with Law Books according to our practice, but if they had searched their inside, they would have found their mistake, when instead of ‘Statutes at large’, and ‘Cooks Reports’, they should see ‘Amadis de Gaul’, and ‘Orlando Furioso’, they would have found the ‘Mirrour of Knighthood’, they would have been much mistaken when instead of Gown-men pleading at the Bar, they found Sword-men fighting at the barriers.

From 1657 he was publishing plays, although his partnership with Henry Marsh, Nathaniel Brook and Thomas Johnson ended after they were accused of pirating an editions of John Fletcher’s “The Scornful Lady”.

He founded the world’s first circulating library in 1660. In 1661 he published a catalogue of the 690 plays published till then in England, which in 1671 he expanded to 806. Kirkman claimed to have read them all, and be ready to sell or lend them, “upon reasonable considerations”, and proposed to publish other plays from the manuscripts he claimed to possess. In the second list Kirkman includes 52 plays attributed to Beaumont & Fletcher, with Ben Jonson the next most productive, and Shakespeare third with 48. It must also be an indication of his popularity that in 1661 Kirkman advertised books for sale at the sign of “The John Fletcher’s Head”, only the second author thought worthy of this, the first being Jonson.

Kirkman appears to have had a penchant for the picaresque sub literature that probably appealed to the coarser end of the market. He was also the publisher of a number of popular works, given more or less accurate attributions. This included The Birth of Merlin, in 1662, ascribed by him to William Shakespeare and William Rowley. This has been described as “a medley in which legendary history, love romance, sententious praise of virginity, rough and tumble clown-play, necromancy and all kinds of diablerie jostle each other”. He also published popular novels including The English Rogue (1665) by Richard Head. At a time when author’s rights were minimal and attributions unreliable, Kirkman was not averse to cashing in an author’s success without involving the author himself. Kirkman himself wrote sequels to this in Head’s name, and additional volumes to other popular romantic histories, Don Bellianus of Greece, and Palmerin of England.

Kirkman and ‘The Beggars Bush’

It is not therefore surprising to find Kirkman attracted to The Beggars Bush play by Fletcher & Massinger. It was published twice in 1661 by Humphrey Robinson & Anne Moseley. Their first edition seems to have been based on a version prepared by Massinger. The second printing seems to have been hurried, as it contains extraneous material, and a notice:-

“You may speedily expect those other Playes, which Kirkman, and his Hawkers have deceived the buyers withal, selling them at treble the value, that this and the rest will be sold for, which are the onely Originall and corrected copies, as they were first purchased by us at no mean rate, and since printed by use.”

Although in editions of other plays printed in 1661 Kirkman denied he had “printed” the pirated edition of The Beggars Bush he primarily a publisher not a printer. He also advertised in the same volumes that he could supply “all the Playes that were ever yet printed” including The Beggars Bush and the list he published of nearly 700 titles is still a valuable resource. Also the pirated version of The Beggars Bush uses an unusual set of type which is used in other plays acknowledged by Kirkman, and in the first edition of The Wits, so the denial rings hollow.

The Wits and The Lame Commonwealth

The Wits, or Sport for Sport included an extract based on Act II Scene 1, of The Beggars Bush, called “The Lame Common-Wealth”, containing the canting exchanges. This may have been important in the distribution of Beggars Bush as a place name . The first edition was first published by Henry Marsh in 1662, but seems very likely to have been prepared by Kirkman before they fell into dispute and litigation. Marsh was a member of the Stationer’s Company, and seems to have acted as printer and bookseller, with Kirkman acting as publisher and editor. It was described as “Part I” but the second part did not appear until after Marsh had died and Kirkman had taken over his business. In 1672 Kirkman re-issued Marsh’s work, and issued an enlarged edition in 1673.

He wrote, disingenuously, that the pieces were “written I know not when, by several persons, I know not who”. He included the gravedigger scene from Hamlet and the bouncing knight from the Merry Wives of Windsor so their authorship cannot have been a mystery either to him or his audience. One of the drolls had previously been published by Marsh & Kirkman advertised as having been played by His Majesty’s Comedians and also by apprentices.

The Wits went through many editions in the next two decades. In the Preface to the first edition the contents are described as :

“Selected pieces of drollery, digested into scenes by way of dialogue; together with variety of humours of several nations, fitted for the pleasure and content of all persons, either in court, city, country, or camp”.

In a 1673 edition Kirkman elaborates saying they are:-

“Presented and shewn for the merriment and delight of wise men, and the ignorant, as they have been sundry times acted in publique, and private, in London at Bartholomew in the countrey at other faires, in halls and taverns, on several mountebancks stages, at Charing Cross, Lincolns-Inn-Fields, and other places, by several stroleing players, fools, and fidlers, and the mountebancks zanies, with loud laughter, and great applause “.

Kirkman recommends his work for performers, specifically those not working in theatres. His preface ends: –

“And now I will address my self to my particular Readers, and conclude. Besides those who read these sort of Books for their pleasure, there are some who do it for profit, such as are young Players, Fidlers, &c. As for those Players who intend to wander and go a stroleing, this very Book, and a few ordinary properties is enough to set them up, and get money in any Town in England. And Fidlers purchasing of this Book have a sufficient stock for all Feasts and Entertainments. And if the Mountebanck will but carry this Book, and three or four young Fellows to Act what is here set down for them it will most certainly draw in Auditors enough, who must needs purchce their Drugs, Potions, and Balsams. This Book also is of great use at Sea, as well as on Land, for the merry Saylors in long Voyages, to the East or West Indies; and for a Chamber Book in general it is most necessary to make Physick work, and cease the pains of all Diseases, being Of so great use to all sorts and Sexes, I hope you will not fail to purchace it, and thereby you will oblige.”

Bartholomew Fair was the great congregation in London. Thomas Blount’s Glossophilia or a Dictionary (1656) defined a ‘Mountebank’ as “a cousening Drug-seller, a base deceitful Merchant (especially of Apothecaries Drugs) that, with impudent lying, does, for the most part sell counterfeit stuff to the common people.” A ‘Zany’ was a tumbling Fool or imitator, often used by mountebanks to draw crowds. The performances were necessarily short, with gaps in the action for sales. In 1630 Sir Henry Herbert, Master of the Revels, licensed a one of these, a Frenchman John Puncteus, to “with ten in his company, to exercise the quality of playing for a year, and to sell his drugs.” Herbert also permitted Francis Nicolini, an Italian, with his company “to dance on the ropes, to use Interludes and Masques, and to sell his powders and balsams.” Such foreign mountebanks might have needed English texts for their players, who were presumably also English.

Kirkman says the pieces were selected because of their popularity between 1642 and 1660, when the theatres were officially closed: –

“When the publique Theatres were shut up… then all that we could divert ourselves with were these humours and pieces of Plays, which passing under the name of a merry conceited Fellow, called Bottom the Weaver, Simpleton the Smith, John Swabber, or some such title, were only allowed us, and that but by stealth too, and under the pretence of Rope-dancing, or the like; and these being all that was permitted to us, great was the confluence of the Auditors; and these small things were as profitable as any of our late famed Plays. I have seen the Red Bull Play-House, which was a large one, so full, that as many went back for want of room as had entered; and as meanly as you may think these Drolls, they were then acted by the best Comedeians then and now in being; and I may say, by some exceeded all now living . . . ”

Kirkman graphically describes the context of these performances in a passage in which he praises the skills of

“As meanly as you may now think of these Drolls, they were then acted by the best comedians; and, I may say, by some that then exceeded all now living; the incomparable Robert Cox, who was not only the principal actor, but also the contriver and author of most of these farces. How I have heard him cried up for his John Swabber, and Simpleton the Smith; in which he being to appear with a large piece of bread and butter, I have frequently known several of the female spectators and auditors to long for it; and once that well-known natural, Jack Adams of Clerkenwell, seeing him with bread and butter on the stage, and knowing him, cried out, ‘Cuz! Cuz! give me some!’ to the great pleasure of the audience. And so naturally did he act the smith’s part, that being at a fair in a country town, and that farce being presented the only master-smith of the town came to him, saying, ‘Well, although your father speaks so ill of you, yet when the fair is done, if you will come and work with me, I will give you twelve pence a week more than I give any other journeyman.’ Thus was he taken for a smith bred, that was, indeed, as much of any trade.”

Robert Cox

Of Robert Cox almost nothing is known beyond this, and the introductions to two short collections of drolls attributed to and published by or for Cox, which refer to him having performed at the Red Bull. One of these In 1653 Cox was arrested for a performance of Swabber, (included in The Wits). This was almost certainly at the Red Bull, a large theatre, where a performance on 9th June was advertised including rope-dancing, and sword-dancing. The notice also stated that “There will also appear a merry conceited Fellow which hath formerly given content” – very similar terms to those used by Kirkman. The news report of the incident says Cox was betrayed by other actors, and that “the Gentry” were forced to pay the soldiers to be allowed to leave the theatre. It also says that Cox had been employed by the Rope Dancers, and appears to have been alone. Although Cox was resident in Clerkenwell in 1647 and died there in 1655 he may well have performed outside London.

Drolls

Drolls continued to be published through the first half of the eighteenth century. The extent to which they were actually performed is an open question. Some of the contents of The Wits were almost certainly edited by Kirkman from the many play scripts he owned. One of the drolls, Singing Simpkin, comprising about one hundred and eighty lines of doggerel is identical with Kempe’s new jigge betwixt a souldier and a miser and Sym the clown, by Will Kemp, entered in the Stationer’s Register in 1595. Some of the other drolls are known from versions which date from before 1620.

Given the loss of so many published and unpublished works others may also have histories which predate Cox and the closure of the theatres. Their informal performance would leave few records. There are some town records of licensing performances which specifically refer to drolls, and the word remained in use until the nineteenth century, although some of the performance may have been puppet plays. However, there is a clear indication of their potential influence in the appearance of part of one Daphilo & Granida, one of the drolls from The Wits in a Christmas play collected from Keynsham, Somerset in 1822.

That Kirkman pirated The Beggars Bush, and chose an extract to include in The Wits speaks for the popularity of the play with a wide audience. The Wits could have been used as a source by amateur or unlicensed performers, and contributed to the distribution of the phrase throughout the country. Such performances would have left no records, but must have been common at markets, fairs and inns.

There is evidence that the texts in the earlier edition were taken from prompt books or performance texts, as they differ from the printed editions.

The Lame Commonwealth is not simply lifted from the play, but includes an addition section of clowning dialogue at the end, which records stagecraft. There seems no reason for this to be there if not taken from an actual performance text. This and several other drolls required six or more players, though some of the roles wee undemanding.

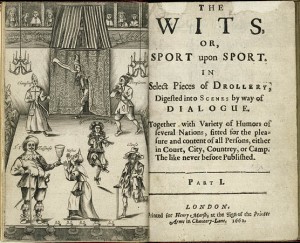

The Wits frontispiece

The Wits is now known mainly for the frontispiece. This is frequently attributed to Wenceslas Hollar, and said to show The Red Bull theatre. Both are unlikely. Astington makes a persuasive case for the artist being a John Chantry, who was associated with Marsh. The print is not described as portraying the Red Bull before 1809, and is inconstant with some of what was known of it.

It shows chandeliers, lighting at the front of the stage, a curtained entrance and various characters. However, it is not a scene from a real production. There are seven characters from six different works on stage at once, including one, The Changeling, who does not appear in The Wits. It may have been intended to include a droll featuring this popular character. Downstage are Falstaff and Clause.

It has been suggested that the images of Clause & Falstaff are derived from the popular engravings of Jacques Callot. That may be right but there is just as much reason for costume designers to use archetypes as for artists. Therefore, the image of Clause may be a faithful portrayal of the character as played on stage.

Clause wears ragged clothing, has a crutch and a mechanism for lifting his left leg to feign disability. This suggests he was a popular & well-known character, and that those playing him made full use of the opportunities for stage “business”. This device, not in the text, suggests that the engraver was using elements he had actually seen, or of which he had been told.

It is likely that The Wits contributed to the popularity of the character of Clause, the King of the Beggars. Although he seems to follow the archetype of the “Upright Man” in Elizabethan “rogue literature”, Clause appears to have no antecedents as a named character before Fletcher and Massinger.

References

Elson, J. J. (ed) (1932) The Wits, or Sport Upon Sport, Ithaca: Cornell University Press

Old DNB and DNB Francis Kirkman

Dorenkamp, J. H., (ed.), (1967) Beggars Bush, Paris & The Hague,

Astington, J,, (1993) The Wits Illustration, 1662, Theatre Notebook 47, p.128

Gerritsen, J., The Dramatic Piracies of 1661: A Comparative Analysis, Studies in Bibliography, vol 11, 1958, p.117-131

Astington, J., ‘Callot’s Etchings and Illustrations of the English Stage in the Seventeenth Century’

Masten, Jeffrey, Ben Jonson’s Head , Shakespeare Studies, 05829399, 2000, Vol. 28, Database: MAS Online Plus

Wright L B (1934) Middle Class Culture in Elizabethan England, Chapel Hill, N C 86-7

Baskervill C.R. (1924) ‘Mummers’ Wooing Plays in England’, Modern Philology, Feb.1924, Vol.21, No.3, pp.225-272, pp.268-272

Lawrence W. J., Review of The Wits or Sport upon Sport by John James Elson The Modern Language Review Vol. 28, No. 2 (Apr., 1933) pp. 254-258

Lawrence, W.J., (1972) Pre Restoration Stage Studies, p.90

Newcomb, L. H., Reading Popular Romance In Early Modern England, Chapter 3, Material Alteration; Re-commodifying ‘Dorastus and Fawnia’ and ‘The Winter’s Tale’, 1623-1843, p.150-156 (Columbia University Prsss, 2002)

Posted: March 20th, 2011 | Filed under: Writers, The Play | Tags: Ben Jonson, Clause, Francis Kirkman, John Fletcher, Literary, Performance Chronology, Philip Massinger, Publishing Chronology, The Lame Commonwealth, The Play, The Wits | No Comments »

Leave a Reply